A few years ago, on a bus near San Jose, a passenger was surprised when a woman on the bus got up and started handing out cards containing the recipe for the Waldorf-Astoria hotel’s famous Red Velvet Cake. when asked why she was doing this, the woman recounted how she hd once stayed at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City and had eaten every day in their restaurant. Every day, she finished her meal with their delicious Red Velvet Cake. The woman loved the cake so much that at the end of her final meal, she asked the waiter if she could have the recipe. He obligingly brought it to her. When she checked out the next morning, the woman was surprised to discover a charge for $350 on her bill. She had been billed for the recipe, which she thought was complimentary. Infuriated, the woman decided to seek revenge on the hotel by distributing the recipe as widely as possible. She printed out hundreds of cards with the Red Velvet Cake recipe and handed them out to everyone she met.

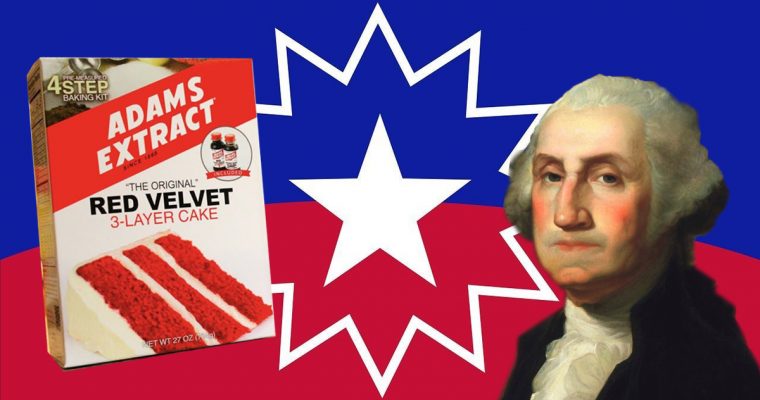

In Beeville, Texas in the early years of the Twentieth Century folks began getting unexpected knocks on their doors. It was a young man selling a bottle of dark brown liquid “Better than anything you’ve tried.” This was John Anderson Adams, who had spend many hours of research perfecting a vanilla extract to make his wife happy. She had been upset with the poor quality of extracts available on the market at that time, and wanted something that could be baked, boiled, or even frozen without losing flavor. The product was so successful that soon the Adams extract company was founded, and the range of available flavors extended beyond vanilla to include lemon, orange, and multitude of others. Adams Extracts were soon available form coast to coast. The soon added a line of food colorings, which would prove very fortunate. When the Great Depression hit, Adams realized he was selling a fancy luxury good. He also realized that people eat with their eyes first, and so he turned to his mother for help creating an eye-catching recipe. The result was the Red Velvet Cake, a photograph of its delightful red was displayed in stores from coast to coast and the red food coloring flew off the shelves. The bright red color lifted spirits during those dark years, and the sales of the food coloring saw the Adams company through the Great Depression.

Neither one of these stories is true. The first is an urban legend recoded by folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand in his 1981 book The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and Their Meanings. The second is a story with multiple variations circulating on the Internet. Red Velvet Cake is a cake with a lot of stories about it. And that raises a question: Why?

There’s a loose consensus about the origins of Red Velvet Cake among food historians that goes something like this: In the late 19th century, raw cocoa powder was commonly used in baking. When combined with acids from buttermilk or vinegar, the powder turns a reddish-brown, and red cakes began appearing in recipe collections by the end of the 19th century. The cake seems to have been an adaptation of European trends that was hugely popular in the American South. These light and attractive cakes were often served at parties, celebrations, and gatherings of upper middle-class women. The creation of artificial food colorings in the early 20th Century produced a brighter, more vibrant red, and the cake spread in popularity int he 1940s and 1950s.

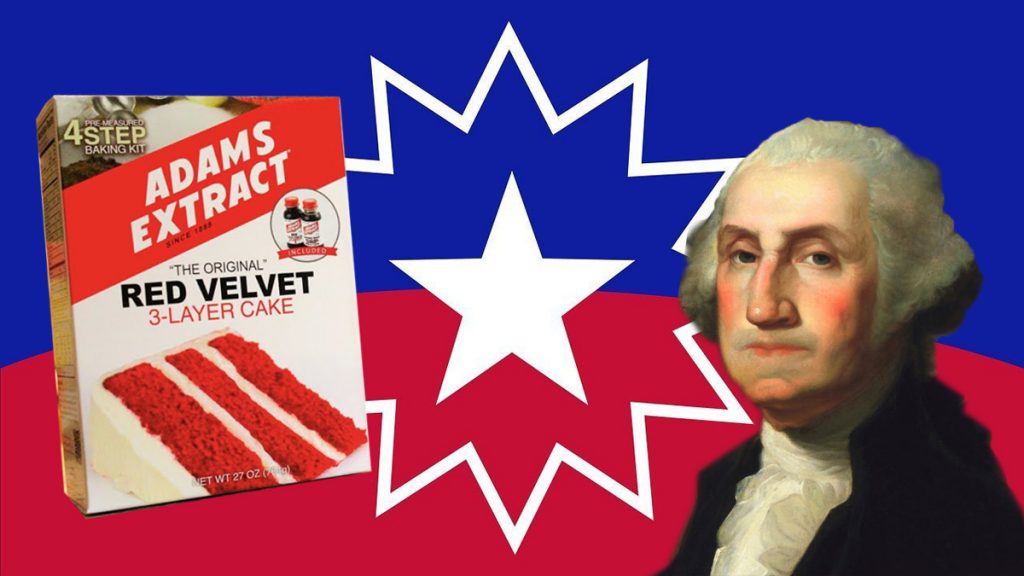

I was recently flipping though my collection of vintage cookbooks and I came across this wonderfully over-he top cover of Helen Corbitt Cooks for Company. This got me thinking about the American Chef Helen Corbitt, who had served as head of food services at Neiman-Marcus in the 1960s when I realized that I had also heard the Red Velvet Cake legend being told about the restaurant at the Neiman-Marcus flagship store in New York. Between the Adams extract legend and the Red Velvet Cake bill, I was aware of two separate legends concerning Red Velvet Cake, and both of them had connections to East Texas. All of this happened around Juneteenth, and that’s when I finally thought that there may be more going on here.

Consuming red foods is part of Junteenth tradition. As food scholar Michael Twitty has documented, this can be traced back to traditions brought by enslaved Yoruba and Kongo peoples brought to Texas in the 19th century. Red Velvet Cake is one of those celebratory Juneteenth foods. And, East Texas having once been part of Mexico, the use of cochineal to produce a bright-red food coloring was already indigenous to the region well before colonization, and well before the infection of Adams Extracts. So it’s very easy, and in fact very plausible, to present an alternative history of Red Velvet Cake originating as part of existing African-American foodways in East Texas, and being introduced into mainstream American culture by a commercial food producer sometime in the 1920s. Something which could easily be described as an act of cultural appropriation.

This alternative history of Red Velvet Cake isn’t alone. There are many legends, folktales, even ghost stories, which seem to crop up around things which are seemingly too innocuous to require a folkloric explanation. And there’s a similarity in these tales. In the twenty years that I’ve been seriously researching folklore, I’ve noticed a pattern which I’ve started calling George Washington’s Dentures.

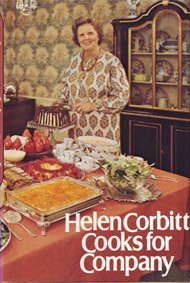

I grew up, as I’m sure many of you reading this did, with the story that George Washington had wooden dentures. This was on your grade school George Washington 101 checklist. Father of the Country, Cherry Tree, Wooden Dentures. I accepted it, unquestioningly, as just part of the background noise of George Washington. It wasn’t until I was in my forties that I learned George Washington’s dentures were not made of wood, but from teeth extracted from the mouths of enslaved people.

It then occurred to me just how actually weird it was that so many people for so many years had been talking about George Washington’s dentures in the first place. If his teeth had actually been wooden, the absolute triviality of that fact doesn’t really bear making central to the historical record of George Washington. But the story exists beyond strict history. It’s serves as adding a bit of humanity to otherwise hagiographic portrayals of the man. It’s a bit of folklore, for someone who is very important to that idea of Folk.

The legend of the wooden dentures was also disguising an act of abhorrent inhumanity. The myth developed as an act of erasure not only of Washington’s slaveholding, but of the very existence of those whom he enslaved.

It’s a story which is, on the surface, too inconsequential to bother making up, and genuinely bizarre in how widespread it is. It’s the absurdity of the very existence of the legend tells us there’s something more to the story.

The Red Velvet Cake legends may well be of the same type of story. The Adams Extracts legend is a folksy tale abut a door-to-door family man who, through plucky hard work, builds himself to financial success. The kind of legend that praises American Capitalism as the best of all possible systems for the simple American willing to work hard. The sort of thing that makes capitalism the kind of thing you can feel good about believing in. But if the actual facts are that Adams Extracts took a Black food, decontextualized it, and popularized it for a White audience, the story is now one of exploitation and erasure. That Red Velvet Cake was a sophisticated and refined dish by the standards of White food culture could not be squared with mainstream depictions of African-American foodways. The Black contribution must be erased from the narrative, and that act of erasure creates a void which is filled in by the invention of the legend.

The idea of folklore is not value-neutral. The very idea emerged from the 19th century German idea of the Volk, which maintained that the stories of common people created a unique narrative for cultural groups, something of a cultural collective unconscious which is distinct for each cultural group. Propagating those stories was in some ways an act of maintaining cultural, and racial, purity.

But we should, by now, have moved past the idea that there’s some well of cultural purity waiting to be dipped in to. Culture is always adapting, and folklore is equally dynamic. Folklore is less an expression of a pure collective unconscious and more akin to another literary genre, one which is just as subject to the larger cultural ideas and trends as any other genre. And in any American narrative, race and identity are always present. And there have only been so many stories about Black People that White People are willing to tell.

Its these dynamics which seem to spur the creation of legends in that George Washington’s Dentures category, where folklore and urban legends recounted in White communities develop to avoid uncomfortable truths, or to disguise and erase Black and minority contributions which don’t fit normative narratives. Often these tories are told about what seems to be trivial matters. The very existence of the story is what tells us that there’s something more there.

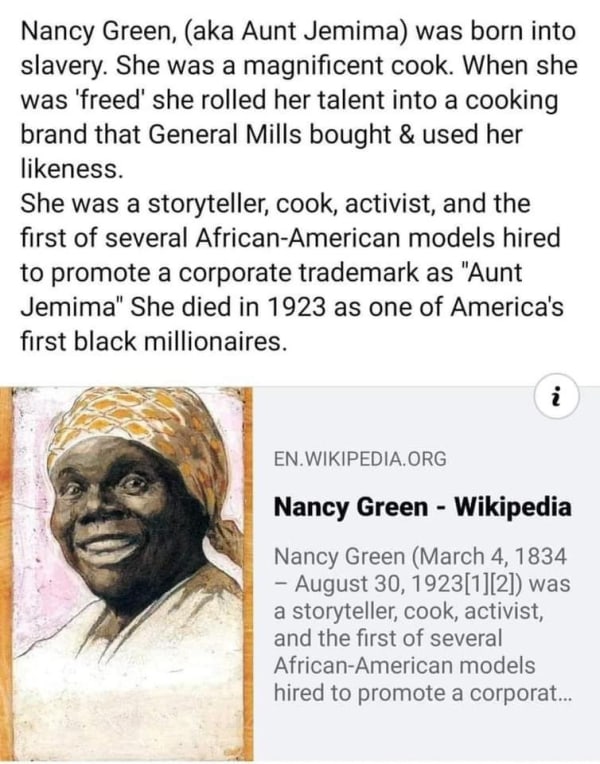

A very recent example of this happened with the retirement of the Aunt Jemima brand. Within perhaps hours of the announcement, a photographic meme began circulating claiming that Nancy Green was the inventor of the brand and had become a millionaire of its sales.

This is simply not true. Nancy Green was a domestic laborer hired to play Aunt Jemima at the 1893 World’s Fair by Pearl Milling Company, who then owned the brand. She continued to play the character while also working as a domestic laborer until the end of her life. She never owned a stake in the company, and certainly never became wealthy as a result of her connection to the brand.

What’s remarkable is how the tune of this story hits the same notes as the Adams Extracts narrative. A tale of a single, gifted entrepreneur who was able, through hard work, to create a new take on an existing household item and use that to make a fortune.

Also like the erasure of Black culinary traditions from the Adams Extracts narrative, The Aunt Jemima meme is an erasure of the real consequences of racism and exploitation in America. It’s a way of saying that racism isn’t a problem by presenting anecdotal evidence that reinforces existing positive narratives about American Capitalism. If Aunt Jemima can become rich, the system works for everybody. That Nancy Green and Aunt Jemima aren’t the same person, and that the brand identity of Aunt Jemima was borrowed from a 19th century minstrel show stock character portrayed by a cross-dressing male actor in blackface are not relevant to the argument. This is folklore calling on the traditions of that early German definition, defining a Folk. But who is and who isn’t allowed to be part of that folk, and whose narratives are allowed to be dominant in the folk discourse forming the identity, is tremendously complex in a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society like America.

Like George Washington’s Dentures, the Red Velvet Cake Narrative and the Aunt Jemima was a millionaire meme are also bizarre in that they even exist. As I asked at the outset, why do these stories exist? What’s so special about Red Velvet Cake? The answer seems to be that folklore in White communities arises at points of interaction with Black and minority communities that don’t fit established narratives. If there’s something which doesn’t fit the accepted narrative, sorties rise up to conceal it. The folklore forms almost like scar tissue around an irritated wound.

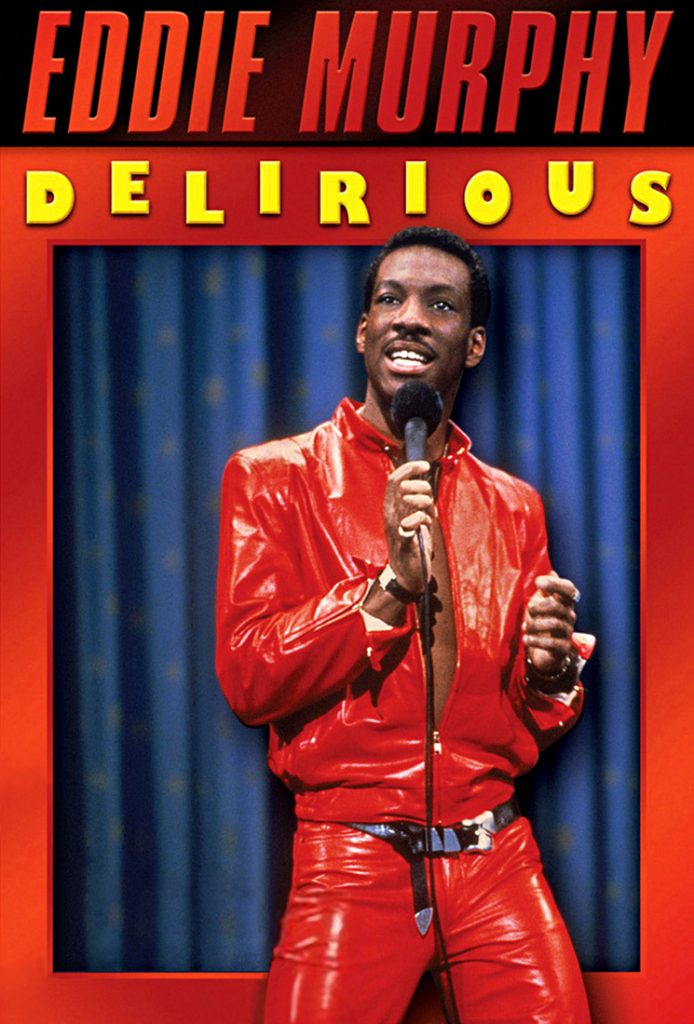

Another Urban Legend in this pattern concerns comedian and actor Eddie Murphy. In a story so widely circulated that Murphy himself has had to end it, the actor is on an elevator in a posh building holding a large pet dog on a leash. A White woman gets on the elevator and, to make more room, Murphy orders his dog to “Sit!”, at which point the white woman immediately drops down and sits on the floor.

The story has been circulating since the height of Murphy’s fame in the 1980s. To look at why this story exists in the George Washington’s Dentures framework, remember that Murphy was exceptional in the early 1980s for brining a largely unfiltered Black voice to White American audiences. In a media environment where the most recognizable Black entertainers for white audiences would still have been Bill Cosby and Nat King Cole, Eddie Murphy was something new. Although it seems somewhat difficult to believe now, the absurd red leather jumpsuit he wore in his Delirious concert film was actually considered sexy in the Eighties. He spoke about race and sexuality from the platform of Saturday Night Live, which was at the time central to the idea of cool among White American audiences. Murphy did not fit conventional narratives and an urban legend grew up around him.

When scar tissue grows up around a wound, it serves as a permanent reminder of the wound’s existence. I strongly suspect that there is more to the story of Red Velvet Cake than just an absurd bill and a cheery story about a vanilla salesman, and I think the very existence of these stories is what tells us that there is.

Too often, amateur folklorists and folklore researchers, particularly those who are dealing with ghostlore or stories of The Supernatural think searching for the truth means tracing a story back to specific events and relating that to the story. While this can occasionally happen, I want to offer up the idea that maybe the real ealing is found in why these stories are being told.

Folklore is a narrative of a cultural identity. But that 19th Century German idea of Volk has, like many 19th Century German idea, turned out to be not the entire picture and not entirely harmless.

When we look at folklore, we are not studying stories from a well of pure identity. Instead, we are looking at narratives that are culturally shaped to define an identity. The idea of having a Folk means that some people are and some are not part of that Folk. There is an in-group and and everyone else in in the out-group. In a folkloric context, both of these groups are defined through narratives. And folklore that develops around interactions between those in-groups and out-groups will carry the impression of larger cultural forces. And in America. those narratives are still very much influenced by concepts of white supremacy and racism.

Understanding these influences is crucial, because ghost stories, folktales, and cheerful little anecdotes like the Adams Extracts Red Velvet Cake story are generally regarded as inconsequential. They’re just silly stories, But because these stories are regarded as meaningless, they are also often allowed to be passed on uncritically.

But these stories still have power. If folklore is a tool of identity creation, if we think of it as a genre instead of a wellspring of cultural purity, we can realize that we have the ability to engage with, and to shape the narrative we’re using to create that identity. And even to turn those stories against the negative forces in the larger culture.

So if you’re hearing multiple stories about Red Velvet Cake, it’s a good idea to ask why you’re hearing multiple stories about Red Velvet Cake. If someone keeps telling you about the president’s wooden teeth, it’s a good idea to ask why they’re telling you about the president false teeth. It’s worth asking if someone is so insistent on pushing a narrative, is that narrative revealing a truth or concealing one? Is there an old wound beneath this story? Am I looking at skin or a scar? Because if there’s a story about something which is seemingly so inconsequential that sticks around long enough to become a legend, it’s probably less a story we’re telling about that thing and more a story we’re telling about ourselves.