This past week I’ve been writing about lost foods. We covered foods that have disappeared and may or may not be reborn, foods that have left traces in history we can follow, and how our relationship to our own lost foods can be used for creativity or self-absorption.

Every one of us is haunted by lost foods. Each meal is a lost meal. Each meal is a unique experience in time, and we never get to stick our fork in the same ravioli twice.

But the experience of eating, at it’s best, engages the senses in a way that no other human activity can, so that the meals we eat can shape our relationship with ourselves, our families, and the way we shape and engage with our culture. The intensity of the experience of eating is unparalleled. Would we have gotten a million words out of Proust if he had just sniffed a lemon?

It’s this engagement with the culture that I need to talk about now, and the path that I want to take to get there leads through a children’s cookbook.

Cricket’s Cookbook was published in 1977 and is from the editors of Cricket magazine, the literary magazine for children.

There’s no way I can pretend to be impartial here. I recognize that I owe an enormous debt to Cricket. It was in the pages of Cricket that I was first introduced to the work of Quentin Blake, Jim Arnosky, Ralph Steadman, Trina Schart Hyman, Edward Gorey, Giles, and even Tove Jansson. Every issue gave me access to the work of an astounding variety of unbelievably skilled writers and illustrators. For a child with artistic or literary inclinations, it was a treasure trove.

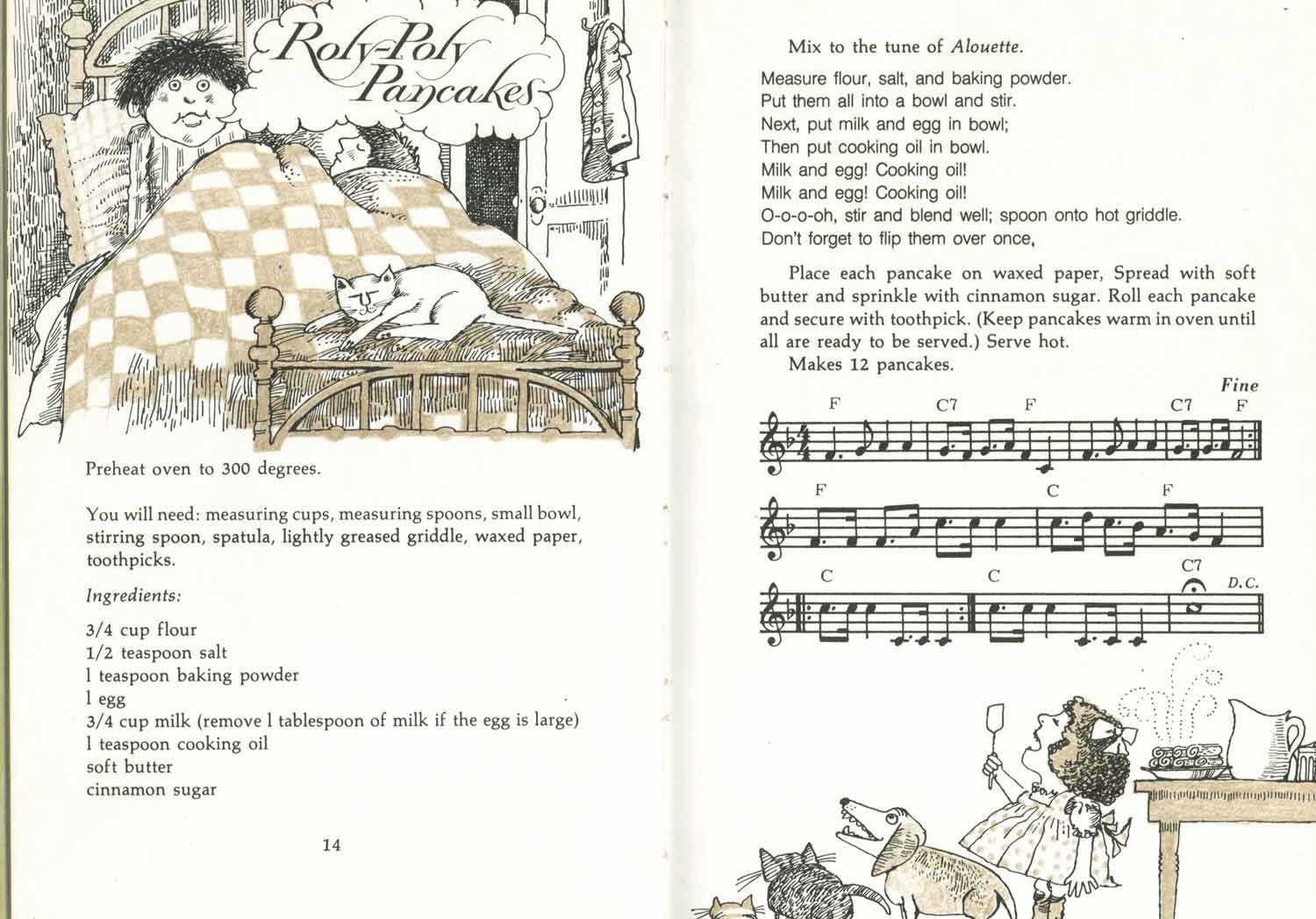

Cricket’s Cookery was one of a small number of books the magazine produced in its early days. Edited by Pauline Watson, and illustrated by regular Cricket contributor Marilyn Hafner, the book is also a genuine delight. The book contains solid, foundational recipes that can introduce children to a variety of basic cooking techniques and equipment. Many of the recipes are accompanied by instructional songs, whose lyrics can take the children through the steps of the recipes to the tune of well-known public domain hits like This Old Man or I’ve Been Working on The Railroad.

What may be most amazing about Cricket’s Cookery from today’s perspective is that this is a cookbook written for children, with the assumption that children will be the ones doing the cooking, unsupervised. There’s a brief note about asking the permission of the top chef of the household before cooking, but no huge warnings about handling hot pans or being careful with knives. The cookbook exists in a world where children were assumed to be able to undertake relatively complex tasks, as long as they had the right tools and room to explore. It makes me wonder if the whole food revolution that America is undergoing at the moment isn’t the byproduct of that brief cultural period when we had a surplus of latchkey kids and no microwave ovens. But the changes that have moved us away from that world have roots that go, believe it or not, even deeper than the Seventies.

One of the most important social changes that’s happened over the course of the last century has been the transformation of the family household from an economically productive entity to a consumer entity. Throughout human history, individual families produced some, or all, of the food that they ate. Surpluses would have been transformed by preserving and stored or sold. A middle-class family would have directly employed one or more servants. Even the majority of city-dwelling households would have had vegetable gardens and a chicken or two.

I’m not romanticizing the past here at all. I’m well aware that for a significant proportion of the people involved, particularly women, this was a world of crushed ambition and drudgery.

On the other hand, if you were to conduct a survey of the modern American workforce and them to describe their lives, I’m pretty sure that crushed ambition and drudgery would show up pretty high on the list for a sizable proportion. Only now the entry bar for that middle class household is set at a crushing amount of college debt.

We’ve gone from being able to produce a substantial amount of our livelihood, to being entirely dependent upon corporations to supply us with every aspect of our lives. Even if you hold down a job, you’re still entirely dependent on the whims of that company for your livelihood. A paycheck won’t grow if you plant it.

I’ve mentioned repeatedly when writing this blog my adherence to the idea that food is culture. As with every other part of culture, the institutions that surround that culture can shape and direct it. The polenta is political.

Earlier in the week, I talked about the breakfast cereal Freakies. Now I’m about to viciously attack that cereal.

Everything I’ve been writing this past week in these lost food posts has been leading up to a single idea. That this:

Is better than this:

We live in a culture surrounded by voices that praise values but condemn value judgements. The same people who say that family values are the most important thing in the culture will turn around a condemn you as an elitist if you suggest that feeding that family Freakies isn’t actually valuing them all that much.

Values are relative. Without judgement, values are useless. And without education, judgement is impossible.

That’s what I mean when I say that a child learning how to make pancakes is better than a child eating a bowl of Freakies. That the knowledge, experience, and autonomy that a child gains from learning how to prepare a meal will make that child more capable, more understanding, and ultimately a better person.

I don’t think this idea should be particularly radical. But the fact that our entire society has been structured so that the time required to let children explore cooking has become a luxury item makes it radical.

Even when Cricket’s Cookery was published in 1977, this sort of time was disappearing. It had been slowly disappearing for over a century, as the household moved from being a producer to a consumer. For the first half of the 20th century, this was hailed as liberation. In the past thirty years, it’s become painfully obvious that it’s just the latest fashion in slavery.

We need to teach our children to cook. We need to teach them to make informed decisions about food. We need to teach them that food is part of their culture, and just like every other part of the culture they have a right to declare judgements about it. But we need to make sure that they have the education to make those judgements good ones.

How do we do this? Public education should be part of the solution, but this is made slightly problematic by the fact that we live in a country that just declared pizza to legally be a vegetable. The corporations that control the production and distribution of food in this country are vastly more powerful than any citizens groups.

Time has also become a luxury. Back when households produced their own food, children, or at least girls, would have been taught to cook because it would have been vital to the economic survival of the household. Now, when we’ve all become entirely dependent on wages to support ourselves, the time needed to teach children to cook has moved being something that was invested for the greater good of the household to something that is spent as a luxury.

One of the most startling moments of my life happened when I was picking figs off my tree at my home in North Carolina. I lived in a relatively poor neighborhood. A young boy whose family had recently moved in next door, fleeing a decaying industrial city up North, was watching me. I offered him some figs. He didn’t understand them as food. He didn’t understand the relationship between plants and food. He had no idea that food could be grown.

This can’t go on.

I’m not willing to accept that only the wealthy have the right to good, healthy food. I’m not willing to accept that the culture of our food can be exclusively shaped by profit-driven corporations. I’m not willing to accept that the values that we bring to the table can only be uninformed belief and not be educated judgement.

I keep saying it, but food is culture. We should have the autonomy to be able to shape that culture. But this can’t mean just expanding consumer choice, because then we just move from having Freakies to having New Organic Freakies. We’re still not any better off.

I don’t want to sound like I’m saying that I have fond memories of Cricket magazine from when I was a child, and I don’t have fond memories of Freakies, therefore my judgement is better than yours. Here’s what’s really frightening me about Freakies, and why I’m choosing to slap the jeremiad on a breakfast cereal that hasn’t been sold for nearly forty years. After the weeks I’ve spent researching this article, watching Flakes, reading about, and listening to that Freakies jingle countless times, I’m starting to think that I remember from when I was young. But I know that’s not possible. Either I’ve been entirely conditioned by the commercial culture, or the advertisers have found an effective way to tap into some fundamental part of my brain, but Freakies cereal has actually started to implant false memories in my mind.

This week has been about lost food. We can afford to loose foods like Freakies. We can’t afford to let these foods make us loose ourselves.

This week has been about lost food. We can afford to loose foods like Freakies. We can’t afford to let these foods make us loose ourselves.

Where do we begin? Cookbooks are essentially instruction books. Cricket’s Cookery gives a good set of instructions for how a more rational, more human world could work. Simple ingredients. Good recipes. Time to make them.

All we have to do is change our entire society around so that we have cultural, economic, and social systems in place that give people and families enough support so that time in the kitchen, time spent on fundamental human activity, is no longer a luxury.

How do we do this? I don’t know. But I know that I need to find out, and start to work on the problem. I also know I can’t do it alone.

Anyone with me?