The idea behind these food in movies posts isn’t really to review the film, so much as look at the role food plays in the movie. With that being said, I can just go ahead and get this out of the way — Flakes isn’t a very good movie. The food they eat in the movie isn’t very good, either.

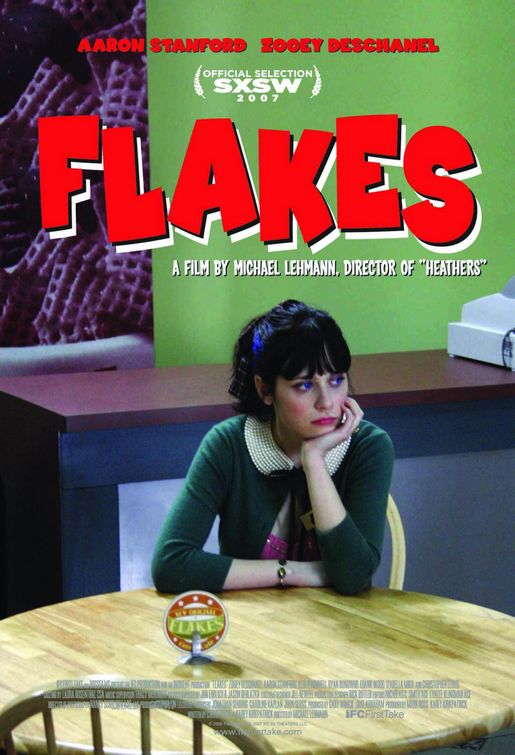

2007’s Flakes stars Aaron Stanford as the manager of an independent cereal bar in New Orleans named, would you believe it, Flakes. The store is owned by a narcotically-addled Christopher Lloyd, who has apparently been paid just to show up in the movie, which he does. Stanford is continually badgered by girlfriend Zooey Deschanel to abandon his life of slopping Corn Flakes into bowls for a crowd of stoners, hipsters, and stereotypically charming New Orleans eccentrics, and to follow his true calling as a musician. Because he’s really an artist. We know this because the movie keeps insisting we believe it, while offering no actual evidence to support the claim. Flakes sets its plot in motion when a straight-laced, uptight character played by Keir O’Donnell opens a rival, clearly-meant-to-evoke-Starbucks cereal bar across the street. Flakes spends its remaining wheels spinning around questions of whether it’s possible to be a bad musician while holding down a low-paying job, whether Stanford and Deschanel’s love will survive, and whether a corporate store that sells overpriced bowls of mass-produced sugar bombs while preying on false nostalgia can ever be true to the genuine spirit of a small, independent store that sells overpriced bowls of mass-produced sugar bombs while preying on false nostalgia.

Flakes almost succeeds as a satire on hipster posing and self-absorbed pst-adolescence, and in more talented hands could have been a cuttingly insightful movie. Which is a pity, because once upon a time director Michael Lehmann’s hands were more talented. He helmed Heathers, one of the most wickedly and deliciously dark films ever to come out of Hollywood. What holds the film back is, in large part, Stanford’s annoying, one-note performance as an unbelievably self-satisfied — I hate to say it, but there really is no other word — douchebag. One of the key things about a protagonist in a film is that it should be someone who you ultimately want to be more or less pro. Here, Stanford turns in a performance as something more like a want-to-beat-around-the-head-with-a-flaming-fixed-gear-bicycle-tire-tagonist.

At the time it was released, critics’ response to the film was overwhelmingly negative. Now, Flakes is chiefly remembered for being called on the carpet for its New Orleans setting. Coming out only a year after Katrina, a movie taking place in New Orleans that focuses on the trivially inconsequential lives of a pair of overgrown adolescents while failing to even mention that the town they’re acting out in has just been completely devastated does seem ever so slightly inexcusable. I suspect the film was shot in the New Orleans because of some tax break or other production deal that came about fairly late in the game, because apart from a few establishing shots the city plays almost no role in the movie. Besides, I know that if I was writing a script about characters obsessed with mass-produced, unappetizing food, New Orleans would surely be the first place that would spring to mind as an ideal setting.

It’s this mass of mass-produced, sugary foodstuffs and the love for them that’s at the core of Flakes. The cool, indie cereal bar Stanford runs specializes in selling bowls of vintage cereal from abandoned brands. I’m going to take it as a piece of movie magic that thirty-year-old boxes of cereal wouldn’t be inedibly stale and possibly toxic, since the film never really addresses this and other very obvious questions of economics that the existence of a vintage cereal bar raises.

A key moment in the film revolves around the acquisition of a box of Freakies, which was apparently a real cereal sold from 1973-1975, and marketed with the express purpose of turning young children on to drugs.

Stanford rhapsodizes about the cereal, saying “This is not cereal. This is Saturday mornings watching Danger Mouse, eating Cool Whip out of a tub.” and calling it “childhood in a box” to which Deschanel responds, in one of the film’s three moments of insight, “Whose childhood? Were you even born when they made those things?”

According to Freakies Fan Websites (oh, Internet, how I despise you) the Freakies, the characters whose existence somehow justified the cereal, occupied a world that had a rich and complex mythology. Furthermore, Wikipedia, the repository of all genuinely useless knowledge, tells us that:

The Freakies were made up of seven creatures named Hamhose, Gargle, Cowmumble, Grumble, Goody-Goody, Snorkeldorf and the leader BossMoss. In the mythology of the Freakies, the seven went in search of the legendary Freakies Tree which grew the Freakies cereal. They found the Tree, realized the legend was true, and promptly took up residence in the Tree which then became the backdrop for all the TV spots and package back stories.

From a pure mytho-poetic standpoint, I’m going to guess that the epic of the Freakies wasn’t up there with Gilgamesh, but that’s probably not the point.

Whose childhood? The debate at the heart of Flakes is whether breakfast cereal, and the childhood memories it evokes are too precious to be allowed to fall into greedy, corporate hands. Never mind the fact that those memories were originally, and deliberately, shaped by greedy corporate hands.

Flakes, like a good hipster girlfriend, continually tries to have it both ways. Deschanel’s character, whose name, incidentally, is Miss Pussy Katz — and is incidental, since in a prime example of the movie’s commitment to indeterminacy, it gives her a ever-so-slightly naughty name, but nobody in the movie ever actually addresses her by it — continually pushes Stanford to grow up and move on. But her version of growing up and moving on involves the pair of them becoming an “art legend” and a “rock and roll king” and traveling across the country in a vintage Airstream. O’Donnell’s character is supposed to be uptight, repressed, and representing the worst impulses of capitalism, but he also comes across as far more likable than Stanford.

O’Donnell also seems to be the only character in the film who has some idea of how life outside of movies actually operates. In the movie’s second moment of insight, he tells a down and out Stanford who has gone to work for the rival cereal bar, “When you were at Flakes, you were rude, self-righteous, sarcastic and full of all that anti-establishment talk… You know, fight the power and all that… Do that here. It sells.”

Flakes wants us to believe that purity of heart is important when approaching a bowl of Froot Loops, and that only a true artist should be allowed to approach a bowl of Freakies. But the thing about mass marketed foods is that if they’re important to you, they’re also going to be important to a lot of people you don’t like very much. They can be childhood in a box, or they can be a product. Either way Kellogg’s gets your money.

When I lived in North Carolina, there was briefly a Flakes style cereal bar across the street from the NC State campus. The business only lasted a few months, and I never went in. As I’ve mentioned, I don’t really like cereal all that much, and the idea of sitting in a room full of people sloppily and noisily chomping on bowls of Cap’n Crunch just held no appeal for me. I would also probably have been a little embarrassed to be seen in public eating cereal.

Which leads us to the final moment of insight in Flakes, which comes after Stanford and Deschanel have been thrown out if Antoine’s, a genuinely good restaurant in New Orleans. Stanford, like many who visit the city, is vomiting on the sidewalk, but in this case it comes from him finding the radical change in diet indigestible. Deschanel, performing her character’s role of clearly stating anything in the scene which might otherwise have passed for subtext, tells him “Cereal isn’t food. It’s baby food.”

Foods can push a lot of emotional buttons, and letting mass-marketed, profit-driven, cynical corporations call the tune is letting yourself be controlled and infantilized. Fortunately, in Flakes, we have a mass-marketed film produced by a cynical, profit-driven corporation to warn us of those dangers.