Smashing Time (1967) is a gentle satire of swinging London, starring Lynn Redgrave and Rita Tushingham as two teenaged girls who go down to the City and “Go stark mod!”, as the film’s tagline says. The film was largely forgotten after its initial release, occasionally playing on TV in Britain, but almost entirely unknown in America until its release on DVD in 1999, as part of the hype surrounding the first Austin Powers sequel. Smashing Time, along with Fathom, Modesty Blaise, and Our Man Flint all hit the shelves in packaging close enough to the Austin Powers look, because if it sold once it can be sold again. It was a slightly deeper connection to the production of Austin Powers that Smashing Time derives its closest claim to modern fame from – there are various versions of the story floating around the ether, but all boil down to something along the lines of Michael York, having been offered the role of Basil Exposition in the first Austin Powers movie, mentioning to the producers “There was this film I was in back in ’67…” and that’s where the production designers for the Mike Meyers’ franchise drew a great deal of their inspiration. This visual connection is very obviously there to anyone who has seen both films, but I think Smashing Time deserves more than to be just a footnote. It’s a very smart, very knowing satire that’s on my list of perpetually rewatchable movies.

I think most of the credit for the film’s success lies with the screenplay by George Melly. Melly was a Trad Jazz singer who moved on to being a social critic, cartoonist, writer, and raconteur. From working as one of the writers on Wally Fawke’s Trog in the daily mail, Melly went on to be a film, art, and movie critic for The Observer, keeping a close eye on the emerging pop and psychedelic scenes. His observations on this era are recorded in his devilishly insightful 1970 book Revolt into Style: The Pop Arts. Thirty years later, Austin Powers would play with at the cliche that Swinging London had become, the nostalgic caricature having long replaced the reality, Smashing Time is looking at the moment from the moment, a view of Carnaby Street from Carnaby Street.

Smashing Time begins with Yvonne (Redgrave) and Brenda (Tushingham) arriving at a gritty St. Pancras station from somewhere up North – a town never mentioned in the screenplay but named “Slagheap” in John Burke’s novelization. Yvonne, the more starry-eyed of the pair, dreams of fame and fortune and everything else she reads of in her favorite teen magazine, Mini Trend. Tushingham’s Brenda is the more grounded of the pair, looking after Yvonne, minding her money, and attempting to keep her out of too much trouble. Yvonne is constantly dismissive of Brenda and keeps putting her down, insults that Brenda absorbs wavering between acceptance and resentment. If the film were made today, the pair’s relationship would probably be called abusive, but I think the dynamic would be immediately recognizable to audience of the time as a Laurel and Hardy dynamic. Yvonne is the bombastic egotist in the Hardy mode, Brenda the meeker, cleverer, Laurel. Even the physical casting of the two actresses seem to suggest this, it’s seemingly impossible to encounter reviews from the period which fail to describe Redgrave as “full-figured” or “an ugly duckling”, up against the wide-eyed, petite, even slight, Tushingham. But the two actresses clearly know each other and know each other strengths. Redgrave and Tushingham had previously appeared together as Helena and Hermia in the 1962 Royal Court production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and on screen in Smashing Time director Desmond Davis’ earlier kitchen sink drama Girl with Green Eyes. The two knew how to work together as a comic duo, and much of their dynamic is each one making room for the other to shine. It’s easy to overlook just how much subtlety goes in to portraying such seemingly superficial characters. Tushingham seems to be doomed to be remembered only as a momentary It Girl from her roles in Dr. Zhivago and The Knack… And How to Get It, and the word most commonly used in the time of Redgrave’s much too early passing was “underrated,” but Smashing Time is testimony of two extremely talented and disciplined actresses capable of giving top-notch physical comedy performances.

And physical comedy is very much the comedy that’s at the core of Smashing Time. Melly, who called himself a surrealist, had a great love for and fascination with silent comedy and American cartoons, particularly Tom and Jerry, as well as the Surrealist’s love for Lewis Carroll. All of these influences are clear in Smashing Time.

The London that Brenda and Yvonne step in to when they emerge from the grimy St. Pancras station is one that is clearly signaled to be on the other side of the looking glass. All of the named characters echo Carroll, particularly Jabberwocky – there’s Tom Wabe, Charlotte Brillig, Bobby Mome-Wrath, Jeremy Tove, a Mrs. Gimble, and even a showing at the Jabberwock gallery. In a scene which is in the novelization but which was apparently never filmed there’s even a white rabbit stand-in, the first person Yvonne and Brenda meet stepping off the train is a Pearly King – a charity society fundraiser dressed in a suit covered with mother-of-pearl buttons, complaining that he’s on a very tight schedule. (Incidentally, the names Brenda and Yvonne seem to be an in-joke of a slightly different sort, these were the in-house nicknames at Private Eye magazine for the Queen and Princess Margaret.)

Melly’s Swinging London is as cruel and as arbitrary as Carroll’s wonderland. Shops appear and disappear, houses are torn down arbitrarily, predatory creatures lurk around every corner, status is determined by a rigid and strictly enforced yet completely unfathomable hierarchy of coolness, and everyone is exploiting someone, being exploited by someone, or both.

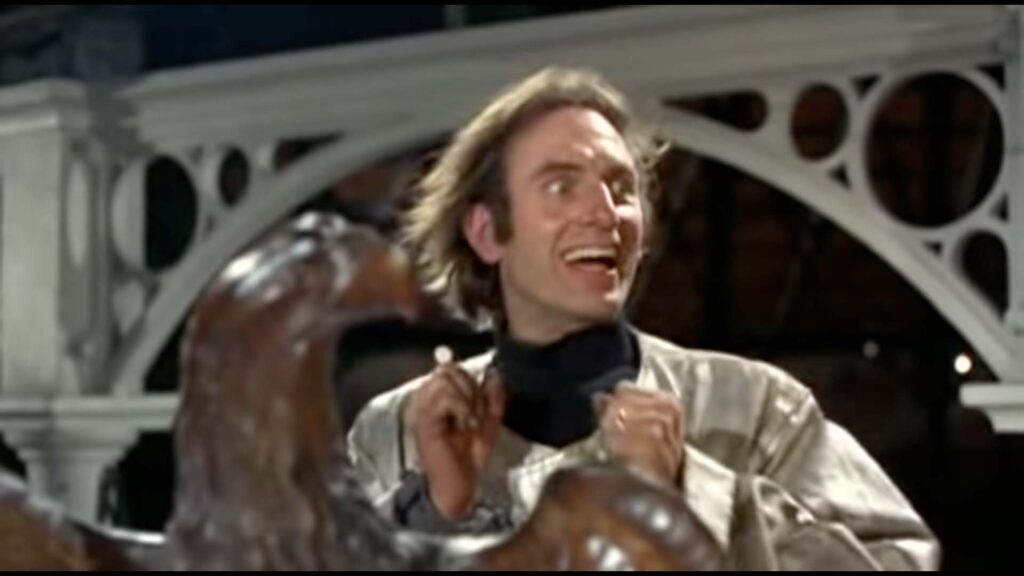

In Smashing Time, it’s Michael York’s Tom Wabe who polices these boundaries. Wabe is “the pace-setting photographer who practically invented the dolly” who photographs the newly-arrived Yvonne for a spread in the newspaper mocking “the out girl in the In Crowd” captioned with “Hair – with this ever come back in style?” and “Skirt – the right length; but are they the right legs?” Throughout the movie, it’s Wabe who has put himself in the position to say who is in the In Crowd, and access to that circle both Yvonne and Brenda will achieve to relative degrees of success. But how they get there is a lot of business. Business in the theatrical sense.

Smashing Time’s title is a double-barreled meaning, it’s not just that Yvonne and Brenda are going to have a smashing time, it’s that the ninety minutes of the movie are a time in which a tremendous number of things are smashed. This is where the movie’s debt to silent film comes in. The plot has been criticized for being slight and episodic, what would be consider the major plot lines in the movie, Yvonne’s rise to fame as a pop star and Brenda’s accession as “the face of the Sixties” don’t kick in until the final third of the movie. The first hour of the movie move from comedy set piece to comedy set piece, a squirt-bottle-sauce fight in a working-class Cafe in Camden, an encounter with lethal art-installation robots at the Jabberwock gallery, an extended sequence of Brenda laying comic traps in a lothario’s apartment, and an extended pie fight at Sweeny Todd, the In restaurant of the moment that serves nothing but pies. It’s a movie built on business.

And much this business might have been lifted from a film of forty years earlier – the two big food fight scenes are even scored with Trad Jazz bits that could easily fit under a Fatty Arbuckle short – but that displacement and recycling of the past is also a central motif of the movie. Swinging London is a place that may have heard it has a past, but isn’t entirely sure what it is or what to do with it.

Too Much, the mod boutique on Carnaby Street where Brenda is briefly employed, is filled with correspondent’s shoes, tram drivers caps, pennyfarthing bicycles, and other decontextualized antiques. The past is there purely for consumption, without sense of its original purpose or provenance.

But there’s an irony in this decontextualization, in that Carnaby Street is only a short walk from Camden, where working class London is carrying on mostly indifferent to the excitement just down the road. But Carnaby Street is dependent upon Camden Town. We get a peek into the shop of Mrs. Gimble in Camden, packed to the ceiling with racks and boxes, every item in which Mrs. Gimble knows the complete history of – the nightgown she sells Brenda to wear as a dress comes from “Titled. Yes… But better than titled.” This is where Charlotte Brillig, who owns Too Much, goes to source items for her own shop. One woman’s trash is another woman’s treasure is another woman’s much higher priced treasure.

Swinging London, as Melly points out in Revolt into Style, was an extremely limited phenomenon, confined to Carnaby Street and nearby Soho, and almost exclusively a playground of the young, beautiful, and wealthy. The rest of London just carried on working while all that swinging was going on down on Carnaby Street. But without that rest of London working all around it, Carnaby Street never would have happened. The kings and queens of Carnaby Street, the pop stars, the mods, are something like The Norman Conquest or The Glorious Revolution – England suddenly finds itself with a new ruling aristocracy, essentially ignorant of the customs and manners of the land. But instead of building castles this time around, this new, self-obsessed and bemused gentry raids the past it has newly inherited and sticks a price tag on it in a shop window, offering it for sale at a price which anyone from the plebeian ranks of the country would recognize as Too Much.

The conflict of the past and present smashing in to one another hits both ways. In the first of those big silent movie set pieces, the conflict is kicked off when Brenda mistakenly switches a bottle of the dishwashing liquid Foam-O with a bottle of Brown Sauce. A customer inadvertently douses his plate of baked beans and sausages with the Foam-O. Another customer enters with a shopping bag filled with bottles, containing everything from fly killer to spray paint to liquid manure, all in identical bottles. The scene escalates as the bag is spilled and another customer grabs the liquid manure and douses his beans with it. (This customer, incidentally, is a young Geoffrey Hughes, best known to American audiences as Onslow on Keeping up Appearances, but who would also part in another significant British pop movie when he was the voice of Paul McCartney in the animated Yellow Submarine movie.) More bottles are grabbed, more bottles are switched, and the scene escalates to everyone in the cafe spraying or squirting everyone and everything around them.

Fifty years later, it’s easy to miss the satire in all of this, because what was then a novelty has become ubiquitous. Everything is in a bottle. An identical bottle. This is the pie fight in the age of mass production – whether its spray paint or brown sauce, fly killer or liquid manure, anything and everything can be a packaged commodity, indistinguishable from the next commodity. And remember, this is a movie where one of the main characters rises to be a pop star.

This scene pairs brilliantly with the pie fight in the Sweeny Todd restaurant, a place which, in tribute to its namesake, serves only pies. This hip Carnaby Street eatery is another historical pastiche, the waiters are dressed as barbers, the waitresses as 18th century street bawds. Low history seen through the lens of high camp. The waiters are presented as a bickering homosexual couple – “You really ought to try shaving before you put on all that flap” stabs one, “Is it the change of life, dear?” cuts back the other. It’s all theater. The high-end restaurant doesn’t use napkins, instead giving customers crumpled-up newspapers. If only they had known about mason jars.

But the camp theatricality of the elite pie-only restaurant comes to the same end as the grimy, working class cafe. Everything erupts into chaos. The difference is in the denouement of the rest fight, we see Brenda sitting outside waiting for Yvonne as cafe boss Arthur Mullard scrubs his own window clean, while at the end of the pie fight in Sweeny Todd, manager John Clive insists everyone send him their cleaning bills. Even in Wonderland, especially in Wonderland, RHIP.

It would be easy to write this tension between the past and present off a just set dressing, except for the action scene that sits in between these two, at the Jabberwock gallery, where the art instillation is the mad machines of Professor Bruce Lacey.

Lacy was a fixture on the art and performance scene in London throughout the sixties and seventies, with close ties to The Goon Show and the performance troupe The Alberts. Lacey’s mix of instillation and performance helped pioneer the proto-performance art events of the late Sixties, “Happenings.” His best-remembered work consists of his robots, remote-controlled devices cobbled together out of old mechanical bits, mannequins, children’s toys, and other recycled historical odds and ends. Lacey’s robots are Rube Goldberg machines built to replace moments of human connection. His commitment to this idea was so great that he constructed a best man robot to hand him the ring at his own wedding. Lacey’s work is preoccupied with the idea of the recycled bits of the past taking on new, and even sinister, meanings in the context of modernity.

In Smashing Time, Lacey is Clive Sword, the sword which cuts open the Jabberwock. The opening which Brenda gatecrashes is a collection of Lacey’s robots, but Melly’s Twist on Lacey’s artwork is that these robots are lethal.

Ladies and Gentlemen – about you on every side are my latest works. Pretty ramshackle you are thinking to yourselves, no doubt. What you don’t realize is that they represent the final status symbol. “And what might that be?” you are thinking as you sip your free but inferior champagne. Well, I shall tell you. Buy one of my statues and you shall be installing the ultimate deterrent in your own lovely home, the threat of escalation in your tiled patio, and the end of civilization as we know it in your sixty-foot L-shaped drawing room.

The statues, controlled from a box built from “old-type wireless sets” may come alive at any moment, tear up their owners valuable collection of “paintings of early Victorian gas works”, and turn the dream kitchen into a nightmare, and “hammer you into the parkay flooring.” “Think of the excitement of living with that over your heads!” Even mortality is a commodity.

In Revolt into Style, Mellly characterizes the Trad Jazz revival as a proto-pop movement:

Revivalist Jazz shared with the later pop movements its spontaneous generation with no initial commercial encouragement: the invention of a life-style through which it expressed not only its own identity but its contempt for outsiders; its eventual decline due to its success with a wider, less perceptive public and the resultant lowering of standards and over-exposure.

Where it differed was in the way it looked back towards an earlier culture for its inspiration, thus admitting that it believed in a ‘then’ which was superior to ‘now’ – a very anti-pop concept.

Pop culture is, for Melly, a country for the young, with rules, boundaries, and taboos but no history.

Pop culture offers the only key to the instant golden life, the passport to the country of ‘Now’ where everyone is beautiful and no-one grows old.

In the country of Pop, the past is a product, just as everyone and everything is a product. Just as the correspondent’s shoes and tram driver’s caps in the Too Much boutique are sold as decontextualized objects – things that are worth having simply because they are amusing – Lacey’s robots are constructed of objects free from context and reassembled into strange, new forms. It’s very pop, but here also very self aware. The drinkers of that complimentary but inferior Champagne shelling out hard cash for these objects do so gleefully embracing the knowledge that their toys will one day bring about their one end. An atom bomb dropped on the entire country of Pop. The thrill of owning one of these sculptures is not the fear that it all one day will end, but the comfort of knowing that it all one day will and it will take you with it. The burden of knowing that one day the In Crowd will be filled with different faces is lifted, and with it goes the awful fear of having to live beyond the moment.

Which leads us ultimately to the most well-remembered sequences in Smashing Time, Yvonne’s rise to fame. Having secured £10,000 after their flat is destroyed in a TV practical joke show, Yvonne invests that money with Pace-Setters Inc, the management company run by Jeremy Tove, played here with a knowing archness by Jeremy Lloyd. Lloyd, who would go on to almost single-handedly shape the British sitcom in the 70s and 80s by creating Are You Being Served? and ‘Allo ‘Allo, also. Lloyd, deeply entwined as anyone in the Swinging London Scene, knows precisely what he’s doing.

Tove is here to turn Yvonne into a product. Not just any product, but an authentic product. He tells Yvonne to “Broaden up your Northern accent. Remember… you worked in a mill” and when Yvonne protests she worked in a record shop, Tove insists “You worked in a mill, baby!” It’s a world where anyone can be famous for fifteen minutes – a year before Andy Warhol got around to pointing it out – but only if they have someone to make them famous. Pop is music as a product, but products still needed to be manufactured.

This brings us to the fantastic hit song Tove produces for Yvonne, While I’m Still Young. In the recording studio, Redgrave sings off-key, off-pitch, and off-tempo. The background singers are a trio of disinterested elderly dinner ladies, contra-bassoons blatt, and because it’s 1967 there’s a badly-played sitar. When the session is finished, and Tove announces “We’re just going to play that back, baby” knobs are twisted, dials are turned, switches flipped, and the result is a perfectly produced pop tune, with the most icily cynical lyrics – I can’t sing but I’m young / Can’t do a thing but I’m young / I’m a fool, but I’m cool / Don’t put me down.

A pop song being open about the cynicism with which it was produced wasn’t an entirely new idea at this point – France Gall had taken Serge Gainsbourg’s Poupée de cire, poupée de son all the way to the top of Eurovision just two years earlier – but in the montage of Yvonne rising to the top of, or at least to number 15 on, the charts, is also the transformation of Yvonne into a brand. From the rest of the movie on, she’s elaborate wigs and outfits with YVONNE branded on them in huge letters. And the montage leads into the next scene of Jeremy Tove taking her and Brenda on a tour of the “turned-on flat in Chelsea,” owned by his company, which he will rent to her for a mere £200 a week. The cycle must continue.

Yvonne’s rise to fame causes a rift in the friendship of the lead characters. In the third act, Yvonne and Brenda split apart, as Yvonne continues here rise to pop fame and Brenda takes up with Tom Wabe, living with him in his canal-docked longboat. Wabe’s photographs of Brenda transform her into “the face of the 1960s,” sparking Yvonne to fits of mad jealousy as she sees her ex-friend’s face everywhere.

This drives us towards the movie’s climax, as despite having been just voted “The pop personality of the week by the paper of the year,” Yvonne is despondent that “No one invites me for country weekends and fashionable weddings,” she asks Tove “How do you do it?” A question which he deliberately sidesteps – like any aristocracy, there is only so much room at the top. Yvonne is dolly of the moment, without the social clout in this new order to ever really be worth being seen with.

Instead, he tells Yvonne they need to throw a party “for the whole of turned-on London – PROs, telly producers, gangsters, pop stars, paperback writers, MBEs. It’ll be the spadiest freak-out of all time. It’ll cost every penny we’ve got left” held in the “scene with the built-in trip”, the revolving restaurant at the top of the newly-constructed Post Office Tower.

Once the pride of the London Skyline, the Post Office Tower kicked off the trend of architectural showoff pieces meant to reassert London’s centrality to Britain, Modernity, and the World. The Millennium Dome, the Gherkin, Canary Wharf, the London Eye, all were descendants of that vision of Modernity Britain, although none of those other ones had a revolving restaurant on top.

Yvonne’s party attracts a stream of rockers, gangsters, archbishops, Twiggy lookalikes, gurus, and aristocracy. There’s a cheering crowd and a press gang at the entrance, while upstairs Yvonne is surrounded by a psychedelically lit, turned-on scene, the walls plastered with enormous blow-ups of her own face. But Yvonne sits at her table alone, sipping champagne glumly. She’s gathered all the In Crowd around her, but she’s still an outsider. A cheap pop dolly and not part of the real ruling class of Pop country. With the arrival of Tom Wabe and Brenda, Yvonne attempts to dance with Wabe to make Brenda jealousy. Rejecting her advances, Wabe pushes Yvonne into the party’s centerpiece, a giant cake with YVONNE written in icing right across the top. The whole room points and laughs at Yvonne.

But Brenda is there to save the day once again, as she sneaks into the revolving restaurant’s control room and finds that the engineers have thoughtfully include a “danger” setting on the restaurant’s rotation speed controls for just such an occasion. Brenda turns the spin of the floor full throttle, and the In Crowd is thrown upon against the walls by that inevitable centrifugal force. The Post Office Tower is revealed to be just another one of Lacey’s machines. The Pop moment is just spinning in a faster and faster circle, going nowhere.

But the two girls, reunited and friends once more, sneak out into the early morning light and Yvonne asks “So what the hell do we do now?” and Brenda reminds her she still has their return tickets. The two friends sing themselves off the screen on their way back to the train station and on their way back home.

Smashing Time is a fascinating little film, and I think a large part of what makes it interesting is that in some ways it is very much of its moment, and that was a very brief moment. Even contemporary reviews noted that the scene the film was satirizing had already by and large passed by the time it hit theaters. So one the one hand it is a very sharp critique, and a handy antidote to the more mythologized picture of Swinging London built up over the years, but the winning performances of Tushingham, Redgrave, York, and Lloyd, and Melly’s wry script, help elevate it above that moment. It’s a movie that bears multiple re-watchings. It is not a perfect movie, the limited budget unfortunately also limited how grand the action sequences could be, and Desmond Davis relies a little too much on the editing to try to stitch the material in the movie’s large silent movie food fight’s together. But other shortcomings become strengths, that low budget meant it was shot on location in London with a minimally dressed set. So it’s a fascinating document of what Carnaby Street and environs looked like at the time. It’s possible to enjoy watching the movie without really paying attention to the action and just focusing on the details in the background. But Melly’s commentary on the country of Pop and its inhabitants is still sharply relevant, and the charisma of the lead actors is enough that it’s also possible to enjoy the movie without bothering to think too much about it at all. It’s worth tracking down.