James Bond, The Cold War, and Camp

For a franchise born out of the Cold War and so heavily associated with it, it took a surprisingly long time for James Bond to engage directly with it. The villains of the Connery and Lazenby years are, with only a single exception, associated with SPECTRE. SPECTRE is, of course, the entirely fictional international criminal organization with seemingly unlimited resources to spend on constructing massive volcano bases and on laundry services for matching uniforms.The Cold War, meanwhile, saw a block of US allied-countries engaged in an ideological battle with the very real (at the time) Soviet Union. The sort of enemy one would expect a spy to be actually spying on.

By the time of Roger Moore’s first outing in the role, 1973’s Live and Let Die, a drawn-out legal battle over the rights to SPECTRE had put use of the organization off limits for Eon productions. But even if they couldn’t explicitly use the name, they used the template. Live and Let Die saw Bond go up against Kananga’s blaxploitation version of SPECTRE (which is incidentally a version which seems better organized well-run than the original) and Moore’s next three outings, The Man With the Golden Gun, The Spy Who Loved Me, and Moonraker each feature a villain out of the SPECTRE mold. It’s only with 1981’s For Your Eyes Only, nearly twenty years after the first Bond movie, that we see a plot grounded in what could pass for actual Cold War spy stuff happening against the backdrop of the actual Cold War.

The plot of For Your Eyes Only is driven by Bond chasing across the Aegean attempting to recover an ATAC machine, a high-tech encryption machine essential to launching Britain’s varied and interesting array of nuclear missiles. The ATAC is a pure MacGuffin, as it brings Bond together with Julian Glover’s Kristatos and Topol’s Columbo, the leaders of rival smuggling gangs with a deep history of animosity towards one another, and ultimately with the KGB leader seeking the device.

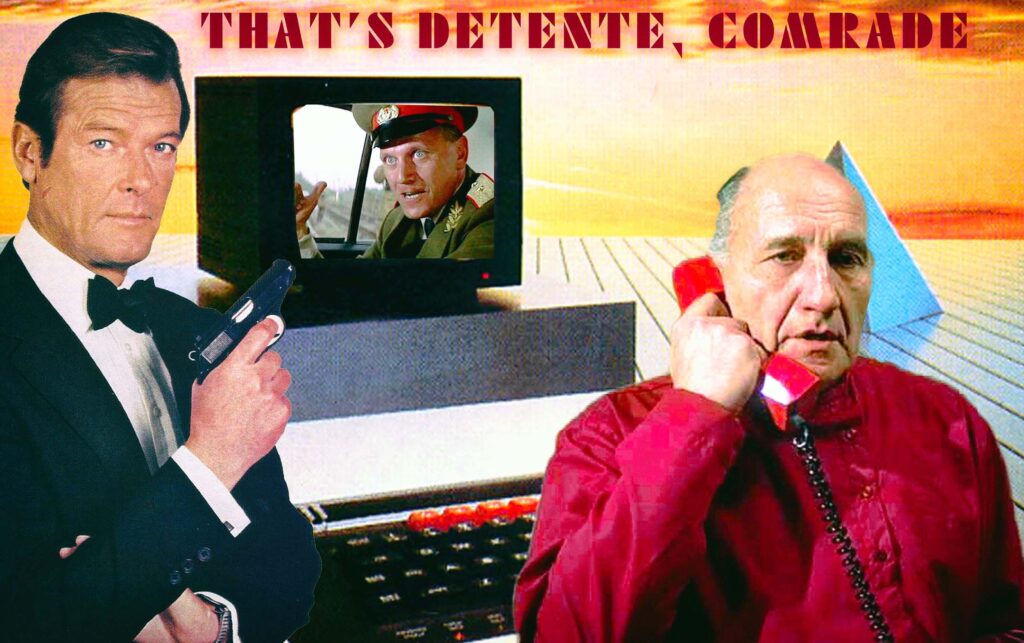

At the climax of the film, where Bond and company have retrieved the ATAC from the now-deceased Kristatos at an abandoned monastery atop a sheer-sided mountain in Greece. Arriving by helicopter for the planned handoff we have General Gogol, head of the KGB, who walks towards Bond with his hand extended, demanding the handoff of the ATAC. Bond hurls it off the cliff, letting it shatter, and tells Gogol “That’s Detente, Comrade. You don’t have it, I don’t have it.” With a laugh and a shrug, Gogol climbs back on board the helicopter and flies away. This round is over, but they’ll have a chance to play again soon.

Gogol, played brilliantly by the late Walter Gotell, was a recurring character, a deliberate parallel to Bond’s Boss M, and who had a part in every Bond movie from 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me and 1987’s The Living Daylights. But for a secondary character, Gogol is surprisingly complex. And it’s in 1983’s Octopussy, Gogol goes beyond just shrugging off a loss and actually deliberately scoring an own goal for the Soviet side.

Octopussy is another MacGuffin-driven movie, though this time we’re served an Egg MacGuffin as the plot kicks off with Bond being assigned to track down the origins of a fake Faberge egg found in the hands of a murdered agent 009. The plot Bond uncovers is probably the most complex, but also most coherent, of any Bond film. A rogue Soviet General, Steven Berkoff’s Orlov, has been replacing treasures from the Soviet archives with well-crafted fakes, selling the originals in the west through yet another pair of smugglers based out of India, Louis Jordan’s Kamal Kahn and Maud Adams’ titular Octopussy.

Orlov’s plan is to detonate a stolen nuclear bomb during a circus show at a US Army base in West Germany. H e expects the explosion and resulting casualties to be mistaken as an horrific accident, and that the massive loss of life will result in cries for unilateral disarmament in the West, leaving all of Western Europe open to an easy invasion by Soviet forces.

Independently of Bond, General Gogol becomes aware of Orlov’s plan and hunts him down in East Germany, where Orvlov is gunned down chasing the train carrying the bomb as it crosses the border heading to the West.

Gogol is a fascinating character in the James Bond universe. As the head of the KGB, one would think he be the villain. But from his first appearances in The Spy Who Loved Me, Gogol is characterized as sympathetic and even as a more humane boss than M. One of his fist appearances has Gogol extending his sympathies to Major Amasova after Bond has killed her lover, a courtesy M never extends to Bond until he becomes Judi Dench.

The Spy Who Loved Me shows Gogol collaborating with MI-6, even sitting at M’s desk when Bond walks in to MI-6’s secret Cairo base. MI-6 seems to have a surprisingly open door policy on letting the head of the KGB walk into their offices, we also see Gogol just casually chatting with M in MI-6 headquarters at the end of Octopussy, and returning there at the end of A View to a Kill award Bond with Order of Lenin. There’s an old school chum kind of feel to the old scene, as if all the players recognize they have ended up on different sides but share common roots. Keeping the game going is the important thing. Which is Gogol’s approach throughout his entire run in the series.

Even in For Your Eyes Only, the only instance where we see Gogol in a role where he’s working directly against MI-6, he takes a very easy come, easy go attitude to his plan being foiled. In Octopussy, during a scene in which we see a Soviet meeting discussing Nuclear disarmament, Gogol is the leading advocate for deescalation and dismisses Orlov’s proposal for a preemptive invasion of Western Europe as “Absolute madness.” Orlov is true believer, someone who views the west as “weak” and “decadent.” Gogol realizes that this is fine as long as you treat it all like a game, but a game that only works if both times agree that the goal is to keep the game going, not to actually win. For either side, actually trying to win is absolute madness.

There’s a common trope in 20th Century science fiction that the discovery of alien intelligence would be the thing that united humanity. Typically, this came in the form an alien invasion, where an existential threat to the planet makes everyone realize that we’re all in this together. Of course, science fiction is rarely looking towards the actual future, and more often using metaphors to reflect a present reality. Nuclear weapons did pose an existential threat to all humanity. And unity was the only way to avoid that threat. And what science fiction was missing, and what (Moonraker aside) James Bond understood, is that we already had that unity. Imperfect as it was, The Cold War worked as a mutual power sharing agreement for the planet.

The Roger Moore era of James Bond has often been described, often derogatorily, as “camp.” But camp is a style which is above all aware of its own absurdity, and as Roger Moore himself has pointed out Bond is a secret agent who can walk into any bar in the world and be recognized by a bartender who also knows what his favorite drink is and how he likes it mixed. Bond is absurd. Just as having every life on the planet one button’s press away from just not being there any more is absurd.

What Moore-era Bond understood is that the people best positioned to keep that destruction from happening were the ones who saw that absurdity. The matching national disasters of the Cold War era, the Vietnam War for America and the invasion of Afghanistan for the Soviet Union, were disasters driven by true believers. It’s the Orlov’s of the world, the one’s foaming at the mouth and wildly over enunciating a word or two per sentence, who will bring us all disaster. Gogol, who in his brief appearance in Moonraker is seen wearing Soviet-red pajamas, answering the phone in the middle of the night, complaining of “problems, problems” while pouring champagne for a woman who we can only assume is his mistress, is the one to keep the game going. Camp is ultimately about loving and embracing absurdity, while still recognizing it as absurd. About learning to love life because it beats the alternative. And God save us from those who really want the alternative. Mutually assured destruction worked because it was mutually assured. True believers could convince themselves otherwise. Belief blots out any sense of absurdity.

One might also take Gogol’s indulgence in the Western decadence with his mistress and champagne as pure cynicism. But camp is not cynicism. As camp delights in life, cynicism delights in merely being right. Orlov’s plan to detonate a nuclear bomb in a crowd of innocent people is far more cynical than Gogol’s pouring champagne for his mistress, or awarding the Soviet Union’s highest honor to a British Agent. The camp Gogol enjoys the game and wants it to keep going, Orlov wants it to end and he wants to win, through any means necessary. Belief, armed with cynicism, is a dangerous thing.

The irony of the end of the Cold War is that the world order that has emerged from it is more dangerous and more absurd than anything The Cold War ever produced. Gogol’s final appearance is in The Living Daylights, a movie with another rogue Soviet General as its villain, only this time around Jeroen Krabbé’s General Georgi Koskov’s plan is solely motivated by money. And though Koskov is defeated, the writing was already on the wall for who the real villains would be after the Cold War. The end of the Cold War was the triumph of cynicism.

The aesthetic crisis of our age is that the forms of camp have been hijacked by the true believers, who are more than familiar with the tools of cynicism. When in the halcyon days of Octopussy, we had true believers willing too use the tools of cynicism, it seems that now we live in a world where the true believers have become the tools of the cynics. We still have the capability to destroy the entire planet, only now it increasing rests in the hands of those who are bent on appeasing a crowd who believe that SPECTRE is real, and probably Jewish.

A camp aesthetic can serve as an a tool for critique and a defense against both true believers and cynics. This is not to say that camp is immune from cynicism (see RuPaul’s Drag Race), but that as an aesthetic which plays in hyperreality, it’s an informative way to view the similarly performative nature of political posturing.

The SPECTRE years invented absurd villains and demanded they be taken seriously. What the Moore era, and particularly For Your Eyes Only and Octopussy did, was to bring that aesthetic of absurdity developed during the SPECTRE years to situations closer to something like the political posturing of the real world. This turned happened 20 years into the film franchise as it took until the 80s for camp to ascend as the primary political language in the English-speaking democracies.

Ronald Reagan was camp. Margaret Thatcher was camp, but they were camp true believers. They embraced the performative tools of camp without camp’s knowingness of its own absurdity.

Was a franchise that had played with absurdity and camp its entire existence aware of this? Well, if it’s any indication, Thatcher appears as a character at the end of For Your Eyes Only. The final scene of the movie has Thatcher reaching out to congratulate Bond on the telephone and being propositioned by a parrot.

This scene is not an outright critique of Thatcherism. What it is is turning a camp gaze onto Thatcher to reveal the absurdity underlying her performance. The red telephone in the kitchen cupboard seemingly connected to nothing, the slapping of First Idiot Dennis’ hand as he reaches into a bowl of raw brussels sprouts, that her dialogue is canned enough that she can carry on a conversation with a bird and not notice it – the absurdity inherent in Thatcher’s political performance is revealed here. And though it is very mild satire, it is satire which is more insightful and has aged much better than most any of the punk songs and foam puppets that passed for satire at the time.

As another depressing side effect of the end of the Cold War, the performative absurdity that emerged during its final years now seems to be the dominant form of political performance worldwide. What is Boris Johnson but Auric Goldfinger with bed head? And this perforative style has even extended into the new and bizarre world of the celebrity businessman. What is Elon Musk but Hugo Drax with bed head?

This has all emerged as the Bond Franchise has seemingly completely abandoned its camp sensibilities in favor of a dour self-seriousness. I’m not willing to propose that a campier James Bond would solve all the world’s problems, but at least it would be better than Quantum of Solace.

But what an awareness of camp and camp performance in politics would do is to expose the absurdity the performances of the newest crop of those dominating the world are built on. The absolute dedication to self-seriousness that has come to dominate not just the Bond franchise, but seemingly all of modern cinema, leaves a gaping hole in the Zeitgeist waiting to be filled by the cynics would use camp to their own ends. If we can only see serious villains in the culture when they’re dressed in desaturated colors and overly-dark lighting, we’re less able to see the clown-colored performative tools when real-life villains bring them out.

Steven Berkoff’s performance as Orlov is camp. It is wild eyed, overly enunciated, and wonderfully over the top. And forty years ago the culture could immediately recognize this as villainy. Now, when these performative tricks are increasingly common among those politicians with authoritarian leaning across the world, it seems that the world is having a lot harder time recognizing this performance as actual villainy. The absence of performative absurdity from the big screen deprives us of a tool for recognizing that absurdity in real life, where it can be genuinely dangerous. The same gaze that revealed the inherent absurdity of the Cold War definitely has something to tell us in this age of multi-faceted and violent absurdity. If the world is going to insist on being this destructively absurd, we need the tools to be productively absurd right back at it.

That’s detente, comrade.