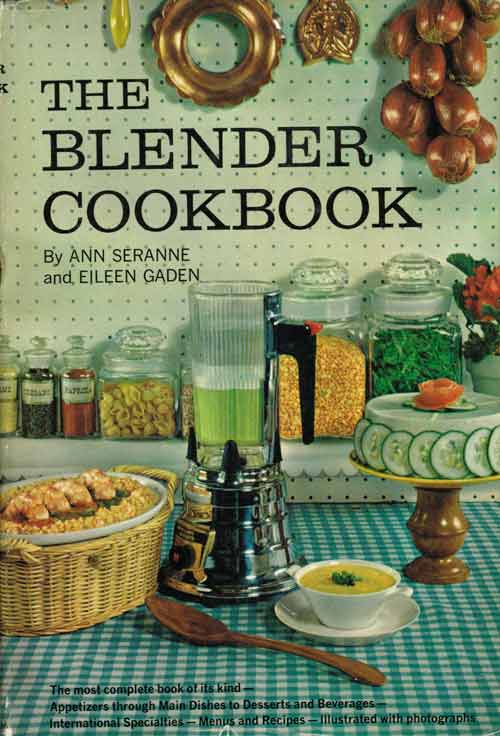

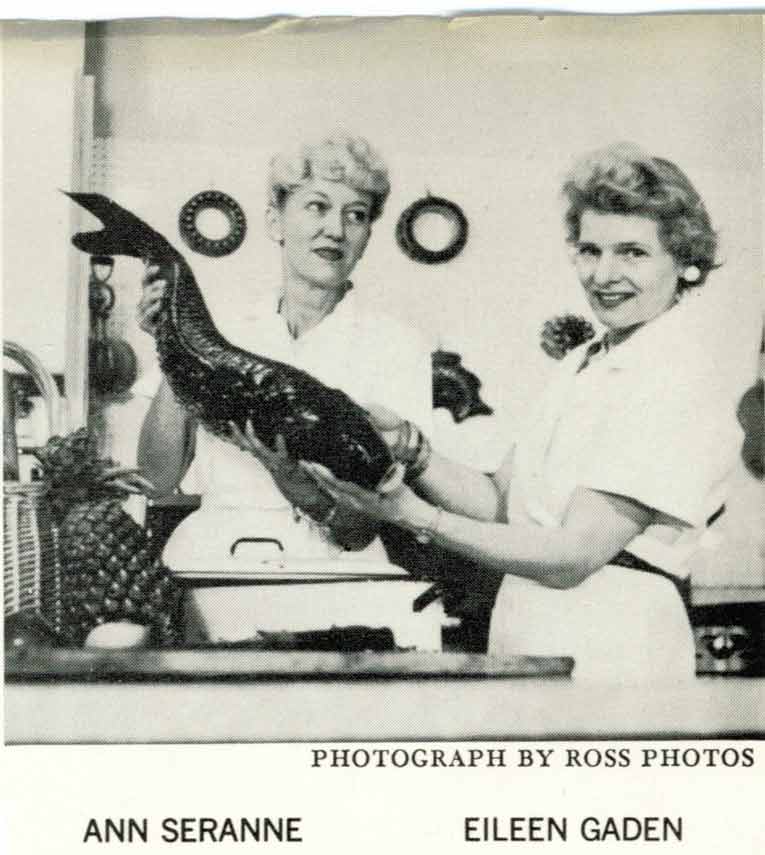

1961’s The Blender Cookbook comes with a surprisingly high pedigree. Written by Ann Seranne and Eileen Gaden, both former editors at Gourmet and both, in their ways, innovators in food science. The pair ran the New York food consulting company Seranne & Gaden, and between them authored dozens of cookbooks. In her 1988 obituary in the New York Times, Craig Claiborne remembered Seranne as having made “the best pies in the world.’”

These women were competent, gifted cooks, and deserve to be remembered more prominently in the history of American cuisine. I have nothing but respect for both of them. Which is why I’m having such difficulty with a cookbook which, for every single recipe, involves sticking a bunch of stuff in a blender and letting it whiz around.

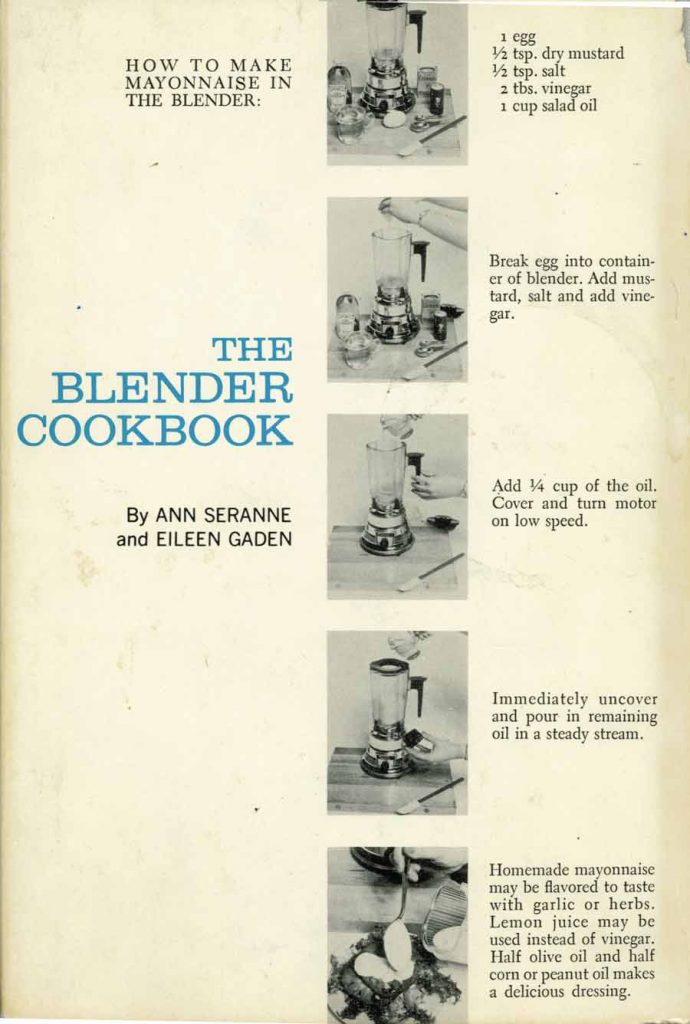

The blender has lost a significant amount of its cultural cache since 1961. Introduced as a home appliance in the 1920s, the blender had primarily been a drink mixer, and it wasn’t until the late 1940s when Hamilton Beach began introducing models with sturdier electric motors that the possibilities of turning the blades on something more substantial than a daiquiri really began to emerge. The 1960s were the Blender’s heyday as an appliance, but it’s dominance was puréed in 1973 when the Cuisinart food processor was introduced to America. With their interchangeable blades and more precise control, food processors soon relegated blenders to the back of the cupboard, only to be pulled out when someone at the party demands a frozen margarita.

The Blender Cookbook captures that brief, simple moment when the blender was king of the kitchen. But, like anything involving a blender, things that start out simple can het mixed up pretty quickly.

A cookbook is something of a skeleton key that can unlock and open a full view of the world at the moment it was written. Cooking is culture, and the cultural changes the country goes through can be read in our recipes.

In my 1953 edition of the Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook, the divider starting off the special tips section has a little blurb that reads “Science has taken the drudgery out of kitchen life,but push buttons can’t do everything.” In my 1968 edition of the book, that same space is taken up with a picture of an egg. The expectation that canned convenience food and shining chrome appliances would transform the world disappeared in that 15-year span between the two. The Blender Cookbook is a product of the moment when that transition was taking place. It’s also reminder that it’s a transition that keeps repeating.

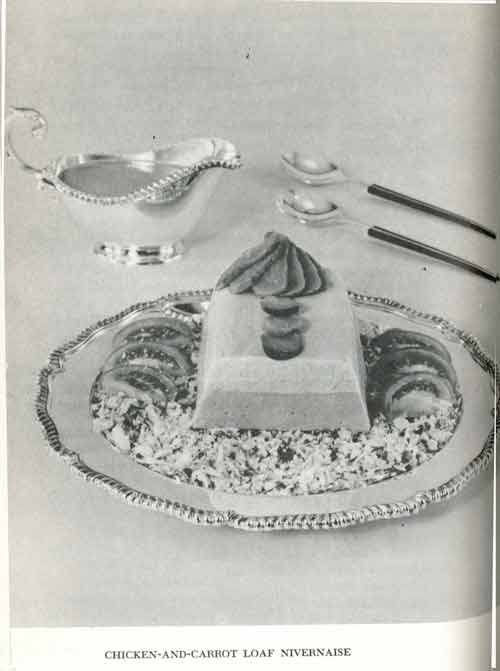

Take this recipe for Chicken-and-Carrot Loaf Nivernaise —

Into container put

1 envelope plain gelatin

1/3 cup boiling water

1/2 very small onionCover and blend on high speed for 40 seconds. Add

1 cup diced chicken meat

1/4 teaspoon nutmeg

1/4 teaspoon pepper

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon dry tarragon

1/4 teaspoon garlic powder

2 chicken bullion cubesCover and blend on high speed for 10 seconds. Remove cover and pour in

1 cup heavy cream

Pour chicken mixture into 4-cup loaf pan and chill until set.

Into container put1 envelope plain gelatin

1/3 cup boiling waterCover and blend on high speed for 40 seconds. Add

1 1-pound can sliced carrots, drained (reserve a few slices for garnish)

2 tablespoons mayonnaise

1/8 teaspoon pepperCover and blend on high speed for 10 seconds. Pour mixture into loaf pan overtone chicken mousse and chill until set. Unmold on cold serving platter and garnish with salad greens and small cutouts of cooked sliced carrots. Serves 6.

When I first read this recipe, I was surprised that I immediately recognized it. I’ve run across descriptions of similar dishes dozens of times, not just in cookbooks but in novels and histories. This is the sort of dish that would have been perfectly at home sitting on a table in Fin de Siècle Paris. Of, course there it would have been a luxury dish that took three days to prepare.

When I read the recipe again, I was even more surprised that I also recognized it from a completely different setting. If, after your chicken mixture in the 4-cup loaf pan was completely set, you were to take it out, bread it, and deep fry it, you would have a perfectly serviceable McNugget.

The kitchen is a battleground in a long-running war between chefs and cooks, between luxury and practicality. And, as in any war, technology can significantly shift the battle lines. With every new invention that replaces some old technique, some luxury foodstuff that once required time, training, and skill is made accessible to the home kitchen. What was once the sole dominion of the chef becomes the common property of the cook.

Packaged gelatin and blenders eliminated the massive investment of time and multiple pot-tenders and prep chefs who would once have been involved in making Chicken Nivernaise. And, once the dish is accessible to the everyday cook, chefs loose interest and move on to new techniques that are even less accessible to the everyday cook. The culture of food as a whole moves along with these lines, and what was once served up to Proust for his pudding is now handed to sticky-fingered children dining under a clown.

The Blender Cookbook is written for cooks. The recipes in the book are, on the whole, perfectly fine. There are a few flavor combinations which would seem slightly out of place on today’s table, but nothing as baffling as a pineapple made of liverwurst. These are solid recipes, written by ladies who were clearly experts in their field. Which makes me feel a little guilty about pointing out the one questions which keeps inevitably popping up as you read through The Blender Cookbook, namely – why the hell are you putting this in a blender?

From the Pecan-Nut Torte to the Scalloped Corn, from the Blancmange to the Broccoli Loaf, from the dips to the desserts, with a lengthy stop over in the Hawaiian specialty menu, every recipe in the book seems to make perfect sense up until you put everything in the blender and let it rip.

If chefs are continually loosing in the war against technology stealing their pride of place, cooks are also loosing in the constant outlay of cash for these gadgets. It’s the perverse economics of conspicuous consumption that has driven cooking in America for the last century.

With every new piece of technology introduced into the home kitchen, a shelling of specialty cookbooks comes down with them. Books on microwave cooking, pressure cooker cooking, crock pot cooking, books on whatever the new gadget is come out with each new gadget.

These books universally promise that the new gadget will result in a significant savings of time and money. As the dust jacket for The Blender Cookbook promises —

With a blender, one can save both time and money at all seasons of the year. It costs only half as much to make your own mustard pickles, for example, as to buy commercial varieties.

Which makes perfect sense. At the time, a blender was going for around twenty-seven bucks, so by not splurging on those 10¢ store-bought varieties, after making only 270 jars of mustard pickles the blender has paid for itself.

These gadget cookbooks also always put forth their gadget as a nearly universal device, able to replace whole categories of kitchen implements. To a man with a blender, everything is a possible puree. These claims of universality tend to be about as solid as the ones on saving money, but that doesn’t stop books being written which include dubious ideas like making meatloaf in a blender.

And that’s how these gadgets get moved to the back of the kitchen cupboard as the next one comes along, and as the foods which these gadgets did actually make easier loose the interest of chefs, the home cooks soon forget them too, and pass them on down the line food snobbery to fast food franchises and chain restaurants. And as each wave passes, books like The Blender Cookbook are left scattered like shrapnel in the thrift stores of America.

Still, I do have to say I admire Seranne and Gaden for being ultimately in the only sensible place in this battle. They were the arms dealers. Always the only real winners in any war.

And, because of what Mad Men has taught us about the workplace in 1961, I suspect that the genuine inspiration and drive behind these recipes may have come from one recipe in The Blender Cookbook that I can recommend wholeheartedly —

Fruit Daiquiri

Into container put

- 3 ounces light rum

- 1 1/2 tablespoons lime juice

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1 cup finely cracked ice

Cover and blend on high sped for 10 seconds. Makes 2 drinks.