Blakes 7 is not an easy show to make any kind of consistent sense of. This is primarily because there is very little in the show that’s consistent. Running for for series on the BBC from 1978 to 1981, this space opera followed a group of escaped criminals led (at first) by the eponymous Blake, attempting to take down the quasi-fascistic Galactic Federation. By the end of the show’s run, Blake was gone, along with all but three of the original cast members, one of whom was then playing a different character. The motivations of the characters got murkier, the scripts got looser, and the sets wobblier. But that’s part of the charm, really. Everyone involved with Blakes 7 clearly knows what they’re up against, and everyone is cranking up the performances to levels of high camp to compensate.

I’ve been watching the series again over the past several weeks. This is the first time I’ve really watched the show with any consistency since it first aired in America on PBS. I was in junior high and was already a devotee of Doctor Who, John Christopher, and any other piece of British Sci-Fi I could get my hands on. Which, in a relatively sleepy southern city in the early 1980s, was not exactly an easy task. I clung on to any scrap I could get. I still have a copy of Turlough and the Earthlink Dilemma somewhere, for God’s sake. When this new series rolled on to my screen, it immediately had the full attention of my uncritical eyes. Going back now, it’s surprising how much of it has subtly stuck with me and how much of it has equally completely disappeared.

The episodes vary widely in quality, and the rules of the universe are rewritten from week to week for plot expediency. There is also very little consistency in characterization, or at least consistency in the ay the characters are written. The performances are a different matter. Given the lack of consistency, two of the pillars of the program, Paul Darrow as de facto show hero Avon, and Jacqueline Pearce as chief baddie Servalan, make a remarkably intelligent acting choice — pick a line reading and stick with it. As long as you plow ahead with delivering every line in as consistent a way as possible, the pieces will fall in to place around you. In Darrow’s case, he’s doing a snarling version or Richard III. Pearce opts for a high-camp sexuality that wouldn’t be out of place in a drag show. Filled out the background with a surprisingly deep pool of talent, all showing up to have fun for a paycheck, and you have enough over-the-top enthusiasm to carry the show for four years. And when, by the fourth year, you’re doing Portrait of Dorian Gray – In Space!, it really is probably the most sensible approach to take. None of it would have worked at all if everyone was taking it completely seriously.

Madame President and one of her dancers.

So why look for deeper meaning in what is pretty much a hot mess? Well, mostly because that’s what I do, but also because I think there is something of an underlying ideology, or at least a de facto ideology, to be found in the universe of Blakes 7.

Most ideologies require good guys and bad guys. The baddies in Blakes 7 are baddies because they are the baddies. The Federation, while it may maintain some o the trappings of a fascist state, never seems to be particularly philosophically driven. The first episode establishes a sort of 1984 type world on Earth, but we’re given very little indication that there’s a central thesis that the Federation adheres to. There’s no creed, no slogan, no indication of official party or party line. The Federation, instead, seems to be the totalitarian arm of a series of extractive industries. There’s a lot of mining going on in this universe.

It’s also riddled with corruption, from the top down and the bottom up. Particularly in the later part of the show’s run, it’s rare to meet anyone employed by the Federation who isn’t on the take or looking to be on the take in some way. The corrupt Belkov in Games, the sexually predatory Reeve in Sand, even the overconfidently ambitious Leitz in Traitor, the whole of the fourth series seems to be populated by mid-level galactic bureaucrats who seem intent on getting everything they can from an ineptly overinflated empire. Even chief baddie Servalan, deposed from the presidency between series, spends the whole of the final series trying to work her way back into power, simply for the sake of having power. Power is an addiction, she confesses in one of the few effective pieces of character study in the entire run, Tanith Lee’s outstanding Sand. It’s an empire that seems to keep going out of momentum, with only a few true believers scattered here and there.

All of this would seem to have something to say about a Post-Colonial Britain in the 70s. But if it does, it’s really only peripherally. And that where things get weird. Because throughout its run, Blakes 7 is rarely interested in exploring why the baddies are baddies. But it is fascinated by the ways in which they are bad. Particularly one way in which they’re bad. If there’s one thing Blakes 7 keeps coming back to, it’s mind control.

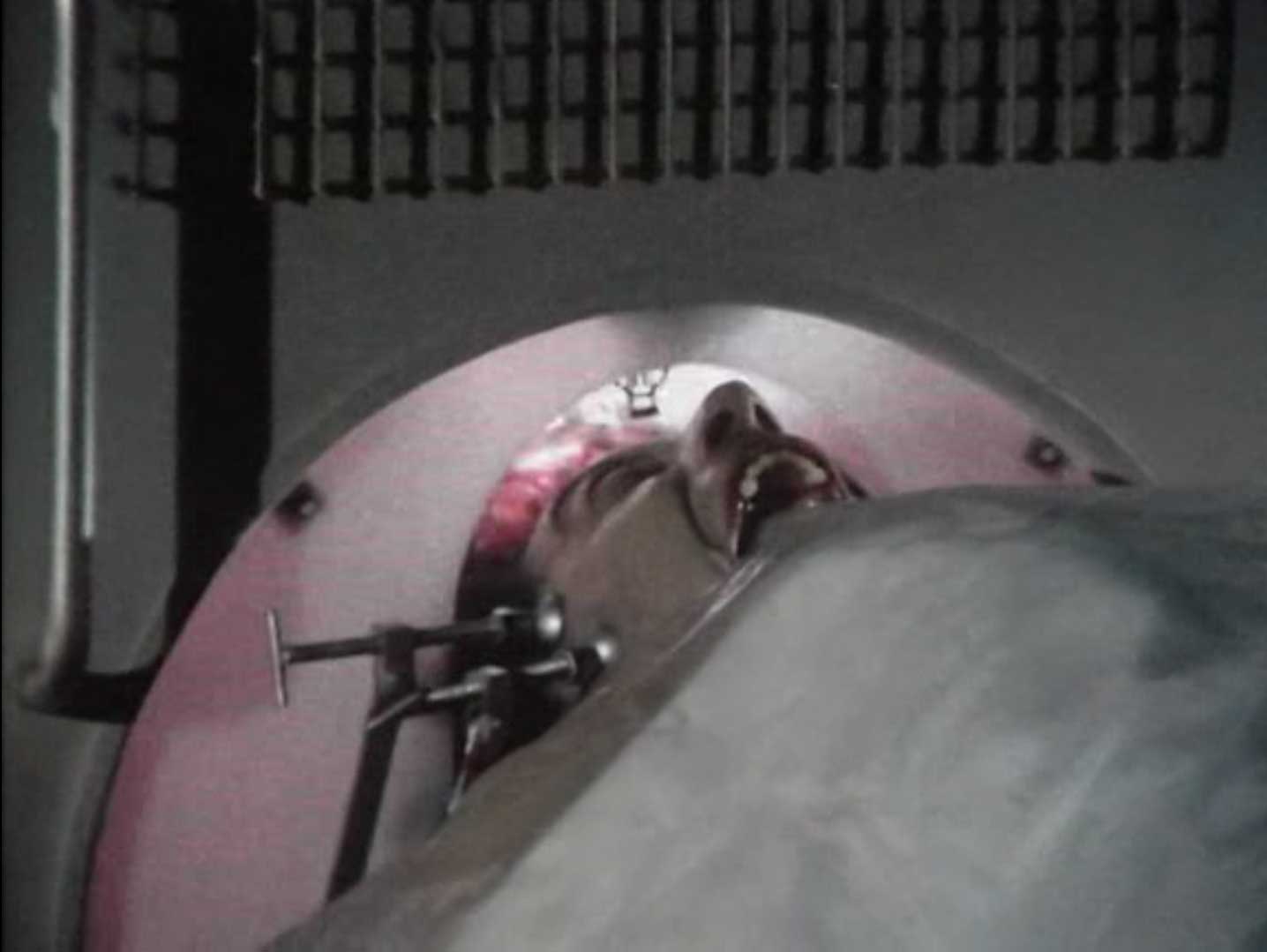

Blake, remembering getting his memory erased.

The very first episode of Blakes 7 focuses on how Rog Blake, former revolutionary, comes back into the fold of resistance fighters. At an illicit meeting of anti-Federation activists, he’s told that he was once the leader of one of the most important resistance factions. As Blake learns the story from a former colleague, he discovers that his cell was betrayed, that he was captured and subjected to some intensive, technologically-assisted brainwashing.

“They put you into intensive therapy. they erased areas of your mind. They implanted new ideas. They literally took your mind to pieces and rebuilt it. And when they’d finished, they put you up and you confessed.”

Captured again, we see Blake subjected to the prodding of a Federation psychologist/brainwasher, attempting to force him onto medications, subjecting him to isolation and brain-altering flashy machines, attempting to convince him that his experiences are not real and rewire his mind in a socially-friendly fashion.

These mind-control efforts are a theme throughout the series. Gan, one of the original seven, and the first main cast member to be killed off, has had a violence-inhibitor implanted in his brain, which causes him severe pain if he ever tries to act aggressively. A plot line in the fourth series follows the widespread use of a Federation pacification drug which makes people open to suggestion and easily controllable. There are various episodes where the main characters and others are subjected to telepathy or other forms of sci-fi mind control. Everybody’s brain gets messed with. A lot. The single, biggest, most consistent threat that the Federation poses is that they make you less you.

The fact that the Federation has so many devices to call upon to do this seems to be linked to the fact that they also seem to have an endless supply of mad scientists. Sometimes ut seems like the only career paths available in the Federation are miner, soldier, or mad scientist. There are mad scientists doing genetic engineering. there are mad scientists creating super intelligent computers. And, of course, there are mad scientists creating new forms of mind control. For all of your population-control needs, there’s a mad scientist to take care of it. And I think in this juxtaposition we can find what, if anything, are the politics of Blakes 7.

In the Series 4 episode Animals, crew member Dayna reconnects with Justin, a genetic engineer who is also her former tutor / lover (Yeah, it was the 70’s. You knew the world “problematic” was going to come up t some point.) for what is basically The Island of Doctor Moreau – In Space!

That got racist quickly.

In Animals, which kicks off when Dayna has been sent to recruit Justin to provide his specialist knowledge to aid the cause. Justin’s specialist knowledge has lately been used to genetically tweak some local lifeforms into a radiation-resistant species who will essentially be used as slaves for whoever gets to them first. Oh, and Dayna gets mind-controlled.

When I say that Blakes 7 does little to engage with Post-Colonial perspectives, I mean that it is really almost blind to those perspectives. The ethics of creating a race to be enslaved are never questioned in the episode. The focus is much more on a “don’t mess with mother nature” take on genetic engineering. The right of the species not to be enslaved is not even given consideration. The big crime the Federation pulls in this episode is to briefly brainwash Dayna to convince her that she doesn’t actually love her kinda creepy, kinda racist, much-older boyfriend whom we’ve never heard of before. The system makes you less you, and that, in the show’s perspective, is a greater crime than the exploitation that the system is built on.

This is one thing that is consistent within the series. To the point that there’s a sentient computer literally named “Slave” as one of the main characters in the final series. Indigenous populations, either human or alien, are routinely depicted as backwards and barbaric. It’s not the exploitation itself that’s the problem, it’s making sure the right people are the ones who are exploited. It’s a show that embraces, though I don’t think entirely consciously, the idea that “There’s no such thing a society” The greatest oppression from the Federation is constantly depicted as being oppression not of individuals, but of individuality. They use mind control techniques to remove a special spark of brilliance that some people possess and reduce them to the level of the herd. Little thought is given to anyone who doesn’t happen to possess that spark of brilliance to begin with. It’s a very adolescent view of revolution, it’s also a highly conservative idea of revolution. The problem is never so much power itself, it’s just that the wrong people happen to be in power.

This is where the mind control, the mad scientists, and the nature of the Federation’s villainy all come together. Blakes 7 operates on a Great Man idea of history. Throughout the inconsistent writing, the show is always clings to the idea that it’s remarkable individuals who change the course of history. When the system is distorted by the wrong people being in power, the population becomes a herd, and men who would otherwise be great become corrupted. Participation in the system is always destructive of individuality. You’re either a mad scientist or an experimental subject.

Again, I don’t think this is an entirely conscious choice on the part of the show runners. Instead, I think what we’re seeing here is just the result of an assemblage of unquestioned assumptions and imported tropes from people writing in a hurry. Dr . Moreau and Dorian Gray are just two of the many times classic plots are pulled in as a basis for Blakes 7 episodes. The show’s entire premise is pretty much The Seven Samurai – In Space! Which is all to say that everyone involved in Blakes 7 was very aware that they were collecting a paycheck. Granted, it’s not as absolutely cynical as some other paychecks that have been collected, but you get the feeling that a lot of Blakes 7 was by and large, thrown together t the last moment, and that’s OK. There are times when you wait for inspiration to strike, and there are times when you just scan your bookshelf and say “Screw it, we’ll just go ahead and do Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – In Space!“

Two remarkably talented actors with remarkably little to do.

The resulting perspective that comes out of this mashup is a strange mix of Boy’s Own adventurism and reactionary Thatcherism bathed in a psot-psychedelic malaise. It’s a universe where the good guys aren’t all that good and ultimately, (spoilers) they don’t win. Really don’t win.

In some ways, Series Four can be seen as a commentary on the series run up until then, and really the entire premise. show creator Terry Nation’s idea for the series conclusion was for the Seven to actually triumph, and have the Federation be defeated. Fortunately, he had moved on to work in America at that time and the show was in the slightly more sensible hands of producer Vere Lorimer and script editor Chris Boucher, both of whom recognized that having a tiny rag-tag band bring down an entire empire was simply too absurd and improbable, even for a show with a ship made from a hair dryer.

The ending is also something of aa commentary on that conservative idea of revolution. If the wrong are in charge, would replacing them with equally wrong people really be that good of a move? Blake could barely get four people and two computers to consistently follow him. Avon was a paranoid, self-interested sociopath. Would a universe run by this crew actually have been much better than the one run by the Federation? You thought James Callaghan was bad? You ain’t seen nothing yet.

Blakes 7 is very much a product of its time, but seeing it thirty years later we have a better perspective on what those times were. It’s a portrait of a country, and a world, very much in transition as the beginning of the end of the Cold War order is becoming apparent. This is obvious even in its design, as the earth tones of the early seasons gradually give way to a putty-grey and glam rock look, with spaceships that would only need an acoustic ceiling and a few ferns to be one of London’s trendiest nouvelle cuisine restaurants in 1981. It’s a universe where someone genuinely thought these guys, the “Space Rats,” looked threatening:

“You know, if we called ourselves the Star Rats instead, we’d be a gang and a palindrome!”

But this design also embodies the reactionary strain that run through the series. Bikers, gangs, glam rock, and young people are all vaguely threatening — yes, I know these Star Rats are clearly in the forties, but according to the dialogue we’re supposed to believe they’re kids. Put all of that together and you get a set of baddies which seem to have been drawn up by someone whose vision of ht future is “Get off my space lawn.”

This is the confused politics of Blakes 7. The show is often described as dystopian, but the overall mood might be more accurately summed up as grouchy. Nothing is right, the future doesn’t look bright, and everyone is going to die anyway. Pulling out classic plots and reworking them In Space! isn’t just a matter of expediency, it’s also a way of saying “See? I told you so.” It’s a perspective of people who feel stifled by the system, but still feel that they are inherently better than those further down the hierarchy. It’s a show that sees there are problems in the world, but isn’t entirely clear on what those problems are and how to fix them. It insists that if things were just better, things would be better. It tries to look for heroes outside the system, but is ultimately more comfortable inside the system. All of which is what makes the show so depressingly relevant today.

That probably that everybody’s going to die part, too.